Sweatshops are workshops where employees are paid low wages for long hours, with few benefits. Common attributes of sweatshops include long shifts, dangerous and cramped working conditions, forced overtime and non-existent job security. Those who protest the conditions would be dismissed immediately. Although they can be found in some Western nations, they are prominently found in poorer countries and some the Eastern nations. They are an integral part of today’s global economy. Sweatshops are commonly associated with China, Indonesia, Cambodia and parts of Mexico and Central America. Goods which require low skill, virtually no technology and little investment are ones predominantly made in sweatshops.

Sweatshops offer a purpose to provide cheap goods to other places in the world, without them, goods would be more expensive. Many activists believe consumers should care where their goods come from, and should try to alleviate the hardships workers go through. Through campaigns, raised awareness and boycotts the like of large corporations who exploit sweatshops are held as responsible for sweatshops. The consumer demand for cheap goods perpetuates the need for sweatshops. However, some would argue that sweatshops are beneficial to the economy and they alleviate poverty. For developing nations, the key is to attract investment, which comes from the likes of large corporations. For nations such as Hong Kong and South Korea, they successfully managed to exploit their low cost advantages in order to grow.

This provides two contrasting demands;

- Consumers should be involved in the likes of economic inequality and injustice, and actively fight against it, no matter how far. These campaigns bring the questions to home and make the issue seem closer, even if physically they are very far away.

- Consumers should leave markets to themselves and still exploit the workers and consumables, perhaps showing some, but little interest. These campaigns show how far away the issue is and how it does not concern us.

The History of Sweatshops

From the 1970s, global markets experienced great shifts in commerce and markets and more jobs were outsourced to developing nations from more affluent ones. As a result, the global market shifted as corporations moved their operations from affluent countries to developing ones to make higher profits. This caused a great divide in that developing nations mainly exported their cheap, raw materials to be manufactured by the developed nations. However, as manufacturing also moved to developing nations at the expense of the workforces in the developed nations, this disrupted markets and job forces.

Now goods and services are drawn from across the globe in order to consume the final product. For example, a pair of trainers can now involve sourcing from one nation, transporting to another, manufacturing the goods and then finally selling. Driven by the Western Nations, now Eastern nations are host to global assembly lines and factories, as the western nations were before them. However, it is worth noting the goods are then primarily re-exported back to the Western nations, and not the host country of the factories.

Definitions

Developed countries – those who developed in the industrial period and nations, and are considered wealthy when compared to other nations. Typically have the secondary, tertiary or quaternary sectors.

Developing countries – those who are ‘developing’ and going through their industrial period and manufacturing. Typically have the primary and secondary sectors.

Redefining wealth in the globe and the extension of disparate wealth.

- HIC – High Income Country

- MIC – Middle Income Country

- NIC- New Industrialised Country

- LIC – Low Income Country

New International Division of Labour (NIDL)

Its name is derived from the fact that, in contrast to the had been before, corporations from the Western nations began to invest in the Eastern nations. Developing nations were more and more involved in manufacturing goods and corporations began to invest in factories and workforces abroad. Through a process of foreign direct investment, Western firms began to establish satellite offices in the developing nations of the global periphery.

Offshore fragments of industry

The rapid growth of offshore services and factories is owed to the advancements in transport, technology and communication during the time. It made it possible to communicate with offices elsewhere in the nation and indeed the globe. Also fragmentation of manufacturing process occurred, where items were moved from one low skilled workforce to another and they would work to assemble the goods. This was possible as well due to the lack of investment or technology needed to assemble certain goods – while more complex work was left to more experienced workforces in nations. While manufacturing processes were outsourced, developed nations began to go through a process of deindustrialisation. Workforces in manufacturing were dismissed in developed nations, and were moved to developing nations.

This began to redefine the new international division of labour (NIDL) from the core (Western) to periphery (Eastern)

As a result of the growing power and necessity of the workforces and factories of the developing nations, new economies emerged, the NICs. New Industrialised Countries such as Hong Kong, Taiwan, Singapore and more – known as the Asian Tigers. These were going through a similar industrial period like that of Britain and the USA, and are continuing to grow.

Subcontracting

Another key feature of fragmentation was subcontracting. Although there were direct investments from the core to periphery, there was also indirect investment through the likes of subcontracting. Corporations would rely on contractors to carry out their work, including building new factories and assembly lines. This proved to be more straightforward than say owning the factory, and with strict requirements and time frames, it was easier for corporations to enlist the help of contractors.

This also passed on the risk from corporations to subcontractors, and they could easily change contractors if they did not carry out their work.

Therefore, how responsible are global brands in their factory conditions and workforce welfare?

Subcontracting became a key feature in the global industry and relinquishes responsibility from the large corporations to the contractors. It is very difficult to know who is accountable for welfare, ensuring health and safety and ensuring the goods out on time. For many corporations in the Western world who outsource, they perceive these sweatshops to be beyond their control and outside of their jurisdiction. This is especially true of they do not own the factory itself.

For many corporations they believe outsourcing is a necessity to business survival – if competitors gain the advantage of exploiting cheaper labour markets, than their business could lose out.

The pros and cons of cheap labour

Is the search or cheap labour to boost profit margins a good thing?

Pros

- Provision of labour – job creation

- Ability to grow the market

- Diversify the market in time

- Become a global power

- Outsourced countries pay more than local ones – improving quality of life

- Wages do increase overtime as firms compete for the workforces

Con

- Exploiting vulnerable workforces

- Poor jobs with long hours and low pay

- No job security

- Factories can easily move from location to location

- Migration from rural to urban – can cities cope with this?

- Fragmentation of operations, and accountability, through outsourcing

Mutual Exploitation

Some critics say that both the corporations and local workforces mutually exploit each other. Corporations take advantage of the cheap labour while workforces can exploit incoming corporations for their work. Some critics argue that the exploitation of workforces perpetuates the exploitation and in fact seals the fate of developing nations, not increase their chances.

Why follow the same rules of business and development when you can look to improve on them? Is exploitation the solution to development or at the heart of the issue?

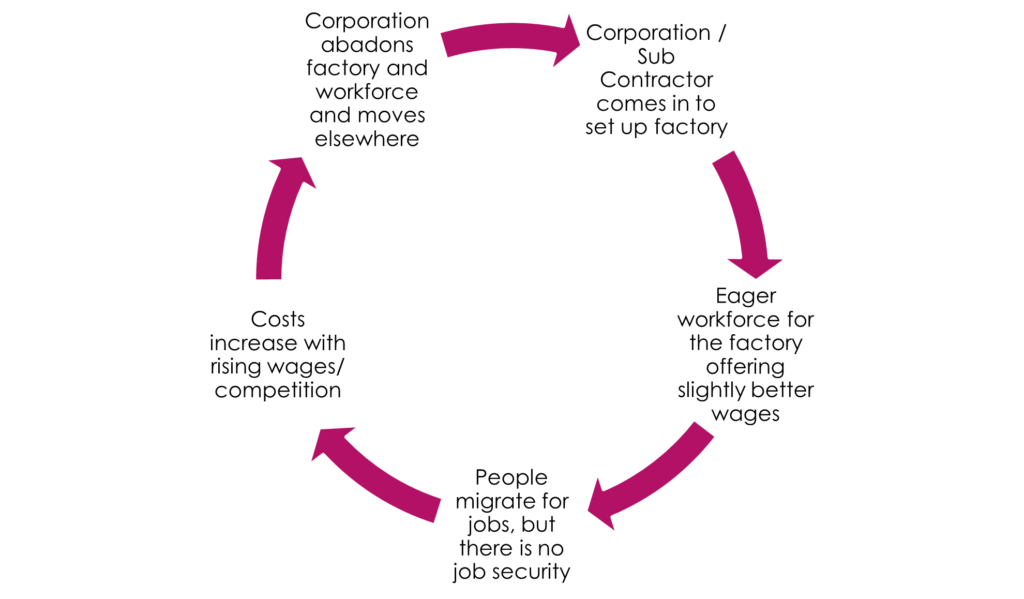

Circle of Decline

The exploitation of workforces can create a circle of decline that subject’s poorer communities to low living standards and keeping them in poverty. Many campaigners say that the world economy is an un-level playing field and the likes of Bangladesh or Indonesia cannot mirror those of the Asian Tigers success. Firstly, the world will always need cheap labour, so it is advantageous to keep those at the bottom at the bottom. Secondly the gap between rich and poor has widened significantly, and there is far much more competition than ever before on the global market. Lastly those at the bottom will not be able to overcome the legacy trade economies such as the UK, USA or recently Hong Kong. Even though through exploitation the likes of Hong Kong and the Asian Tigers became a global power, the share of the Western nations increased fourfold, while those in the poorer nations remained stagnant. It appears that exploitation therefore only profiteered one side.

Campaigning against Sweatshops

Many accounts from sweatshops are the same, working long shifts with little or no break, feeling intimidated or scared of losing your job and not a lot of pay for the work that is done. There have been accounts of child labour in Cambodia, forced or prison labour in India and verbal and physical violence in China. This is coupled with violations of health and safety, operating dangerous machinery, pollution and environmental hazards and appalling sanitary conditions in the work place.

For many campaigners, the solution is to bring the message home about how dependent Western nations are on sweatshops and how they are the reason goods are so cheap and how we exploit these workers from buying these products. In many cases campaigners drop names of large corporations and retailers who are capitalising from sweatshops. They will coordinate campaigns to raise awareness, demonstrate outside shops, lobbying of politicians and arrange boycotts of goods.

Are we to blame for sweatshops and the poor, dangerous conditions of them?

In the 1990s the anti-sweatshop campaigns really gain momentum as companies began to shift their operations. They began to target the big, known brands such as “No Sweat”. These campaigns were the starting point of bringing the message home that we are to blame for the conditions and how we can change them. If corporations have the power to monopolise the market, dictate where goods are made and sold, then they can also determine the conditions of the sweatshops.

Campaigners highlighted how corporations moved their operations to locations where workers had fewer rights and lower pay, essentially a ‘race to the bottom’. Bringing this issue to the audience and consumers effectively lessened the distance of the sweatshops. By highlighting our own social responsibility and accountability for the production of these goods, paying for them and demanding them, we are responsible for these conditions too.

The question with sub-contracting and alleviating responsibility meant that corporations and consumers did not feel responsible for the condition of sweatshops. Campaigners sought to trace the responsibility and highlight it is a global issue that everyone is responsible for – not some distant issue that does not affect us.

Activity

Complete some searches on anti-sweatshop campaigns, such as ‘No Sweat’. Campaigns still continue to this day and have taken many forms. Nike, Gap Inc and Primark have all been targets to campaigns.

Corporate Connections

Corporations are the ones that directly benefit from capitalising on sweatshops, and through subcontracting, alleviated any responsibility of the sweatshops. Subcontractors were enlisted due to their competitive edge, quality and reliability, not necessarily whether they abused worker rights. Campaigners could link however how corporations benefitted massively from the misfortune of the workforce and as such, this began to destroy their image and reputation.

Corporate Code of Conduct

The codes themselves amounted to an explicit acceptance from corporations that they were responsible in the development of sweatshops, and the workforce who created their products but not directly in their name. many of the codes covered typical conventions including minimum working age, health and safety measures, hours of pay and pay and working in a way that workers knew their rights. Although these codes of conduct address key issues of welfare and safety in the workplace, they vary greatly amongst companies. The freedom of association and right to collective bargaining is often overlooked, and most are top down affairs where the corporation has instigated these policies with little to no say from the workers. Some have been drawn up by NGOs, trade unions, government bodies and human right officials. The act of monitoring also has a variety of forms, including ‘in house checks by staff or unbiased bodies.

Levi Struass was the first to create an official code of conduct in its ‘Business Partner Terms of Engagement’ (1991) after it was accused of using forced prison labour. Nike also created its own in 1992 after negative publicity about labour malpractices. Gap Inc provides the most comprehensive monitoring in its Social Responsibility Report (2003). It operates with an in house team of 90 compliance officers over 12 months. It conducted around 8500 factory visits, a majority were in Asia. It noted that few factories fully met the criteria, and many in China, where most of the sourcing comes from, experienced lots of verbal abuse and coercion. However, in other areas environmental hazards, unsafe machinery and so forth were not found. 136 factories had supply deals terminated at this time due to violations of the above.

Corporate codes of conduct are only a small step to ensuring compliance and welfare in the factories. It also is a tool to counter claims of sweatshop exploitation. Oxfam and the Clean Clothes Campaign however argue that due to demands from the corporations, such as turnaround times, flexibility and lower prices, they create the dangerous atmospheres they are trying to tackle. Therefore, in order to eradicate sweatshop and dangerous working styles and environments, corporations need to provide realistic time frames and reduce the demand.

Activity

Have a look at some of the largest brands and research their supply chains, Code of Conduct and social / corporate responsibility. Websites will outline a business’ Corporate Responsibility or dedication against Modern Slavery.

Responsibility for Sweatshops

It has been argued that large corporations are to blame for the creation and existence of sweatshops, pushing for higher profit margins, meeting demands and more. Their codes of conduct also suggest they believe they are somewhat responsible for maintaining sweatshops and monitoring their conditions. However, with the constant race to the bottom and to exploit poorer communities, it is difficult to solely blame the corporations. The codes of conduct can simply be seen as a way to generate good publicity to negate the bad and nothing more. It is clear that not every factory complies with standards, standards created by the demand from corporations. Some argue that these conditions are necessary to alleviate poverty and give those a chance to better their living standards.

If left alone, the global market will continue to exploit the less fortunate at the benefit of the most affluent. The spoils of globalisation will remain with the corporations and those working would continue to do so in poor conditions. Corporations are only to change if market pressures and negative publicity threatens their profits, so they may share their wealth with the local population in the form of wage increase or other such improvements. The rise in living and working standards therefore are not from goodwill, but profit protection. Some argue this is necessary to reduce poverty. It is the responsibility of the workers and countries to attract foreign investors in order to create a positive circle of growth, like with Hong Kong.

Pro-market lobbyists say that the anti-sweatshops campaign is irresponsible and damages trade as it prevents profiteering and development in the deprived areas. It also claims that if consumers demand more from corporations in relation to welfare and wages increases, it also could implicate the jobs of workers as the contractors will outsource to even cheaper areas or will make workers work longer in order to meet targets.

If campaigners are worried about poverty, are they not concerned with other sectors that people in poverty work in such as farming or other low paid, low skill jobs?

Political Responsibility of Sweatshops

Whereas legal responsibility involves assigning direct blame for outcomes, we have seen that sweatshops are a production of a myriad of decision makers and responsibilities shared by many. Shared responsibility for events elsewhere is political, because little will happen to change the sweatshops unless consumers, workers, managers, bureaucrats and stakeholders all take collective action to persuade the decision makers. Everyone is involved, including the workers because it is such actions that gave rise to the creation of them. Of course not all actions are the same or carry the same weight. Consumers can spend elsewhere to exercise their power, NGOs can help the vulnerable and so forth. Responsibility does not arise through exceptional circumstances but from common and mundane action, including buying and selling.

We need to question ‘business as usual’ if such means that the consumers get cheap consumables at the expense of the workers. If we demand cheap clothing and goods which prevent workers from a basic wage or standard of living, then we should reflect on this. Us as consumers need to consider what we are willing to pay for goods and the conditions for which they are produced. It is not just the responsibility of affluent nations either to bring about change, the workers themselves need to mobilise to challenge their oppressors. If everyone acts together than sweatshops can be eradicated.

What role does distance play in responsibility?

The reason why sweatshops have gone unnoticed is by the distance and the lack of awareness surrounding them – they were a hidden phenomenon that only factory owners and corporations were aware of. The physical distance plays a role in relinquishing responsibility from corporations and consumers, however campaigners have tried to bring the issue home. We are so globally connected that are actions cause a reaction. The physical distance plays a role in how we view the issue, respond to the issue and attempts to resolve the issue. When it comes to matters of global injustice, the distinction between what is near and far is not best defined by physical distances but instead the global connections and networks, both economically and politically.

Case Study: Nike Inc.

Is a sportswear firm that was one of the forerunners of outsourcing its work force. In the early 1970s it established a network of contractual relationships with factories in Taiwan and South Korea to produce its shoe range. Nike maintained a close, but not deep relationship with most factories, with keeping close ties to its top end rages. A decade later it also had ties with contractors in China, Thailand and Indonesia in order to further diversify its assembly line. By the 1900s Nike Inc. had an extensive network of contractors and suppliers (c. 800), with most of them in Asia. Due to this Nike Inc. could produce c. 175 million pairs of shoes each year (2003).

Case Study: Gap Inc.

Again, like Nike, it has numerous ties with contractors and factories in Asia, totalling 2000 (2004). In the same way the assembly line is fragmented across numerous factories and operations, and goods pass many hands before reaching the shop.

Sweatshops and Political Responsibility, Iris Marion Young

- The argument for responsibility and injustice of sweatshops by the agents who work there is a novel one.

- Assigning responsibility derives from the legal reasoning about guilt or fault. Under this model, you assign responsibility to agents who can be shown to be connected to causation.

- Agents can be an individual or corporation for the purpose of assigning responsibility.

- Responsibility is undermined if the agent was coerced, not free or involuntary. This responsibility is then passed onto an agent who causes the coercion.

- Strict liability holds individuals liable for an action even if the outcome was not intentional, as the agent should have weighed up the consequences.

- The liability model looks back through history in order to assign blame or responsibility. It can also absolve responsibility from some agents.

What has this to do with sweatshops?

The consumers therefore are not responsible directly for sweatshops, even though they are the end user/ target. They are connected to the sweatshops indirectly, and are a product of a highly mediated fashion industry with market relations and complex structural processes.

4 features of political responsibility

- Political responsibility does not mark out and isolate those who are considered to be responsible

The blame model of responsibility distinguishes those who are responsible and those who are not responsible by implication. It isolates one individual or agent for blame, and this is important for criminal and tort law. Blame can be assigned to an individual or collective, and collective responsibility can distinguish those who have done the harm and those who have not. However, that said, although you can blame some for the labour conditions it does not necessarily absolve others.

- Political responsibility questions ‘normal’ conditions

When it comes to finding our wo is liable, what is considered as wrong is generally a deviation from the ‘baseline’. We accept that the situation exists, al be it not ideal. A crime is an action that is considered as legally and morally unacceptable, based on the collective opinions. Harm is a deviation from what is considered ‘normal conditions’ and punishment or compensation aims to restore normality. Consumers and corporations should re-evaluate what they consider as normal and challenge convention is necessary to relieve social injustices. Is the ‘business as usual’ model socially and morally acceptable?

- Political responsibility looks forward rather than backward

Blame and praise are backward looking actions, taking into consideration hindsight. The actions have reached their goal, in the case of sweatshops, cheaper goods and services. However, we can look at these actions and prevent them in the future, causing reformation. Taking political responsibility in relation to social structures looking more towards the future than the past. There is no point in seeking compensation as the ties and links to blame are so casual. Our actions contribute to injustice as we know and understand the structural processes in place, however it also means we can change the processes.

- Political responsibility is shared responsibility

If injustice is a result of structural processes we are all involved in, then change relies on all parties and stakeholders. Working through state institutions is often the most effective means to cause change, but it is not the only way. Information sharing, campaigns, monitoring, media and more can raise awareness and hold manufacturers to account for the conditions. Political action will involve public dismay and disobedience, as well as collective action, will cause change. The victims of harm also have some political responsibility to improve their conditions. When people feel blamed they may act defensively, perhaps blame others or make excuses, and this blame-game does not necessarily facilitate change. Distinguishing political responsibility from blame allows for a collective action

Activity

Do you know the cost of your clothes? Look at your clothes and remember how much you spent. Now look at where the clothes were made. Do you think the worker was paid an honest wage?