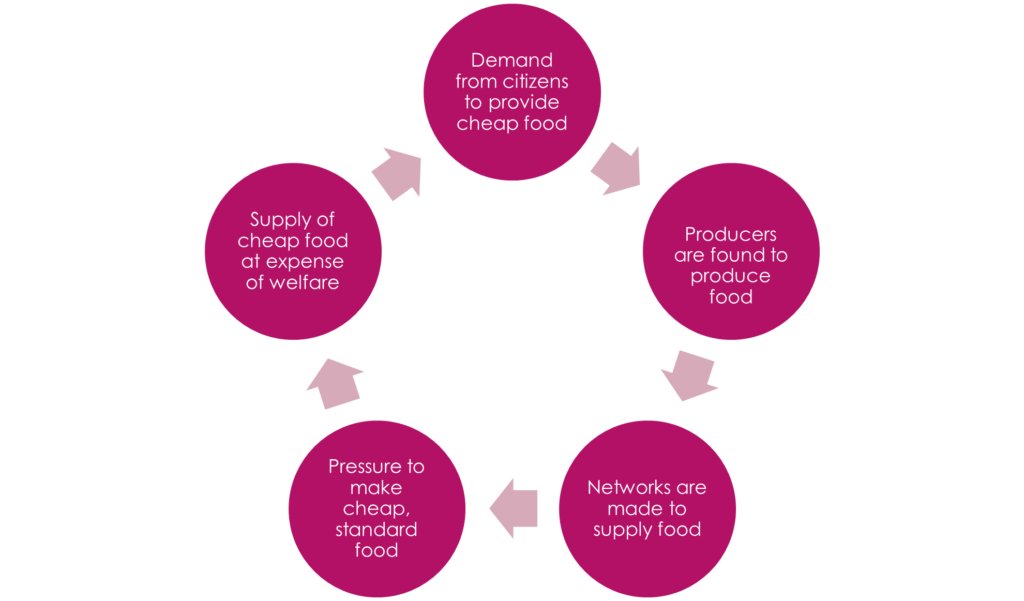

Markets and global trading seems to be at the mercy of multinational corporations (MNCs) and a degree of regulation with the World Trade Organisation (WTO). Even though trading and consumption is undertaken by individuals. Market forces leave little room for social justice and welfare, environmental concern or any other ethical considerations. However, our shopping habits and lifestyle choices impact people around the world and have social and environmental consequences.

There are a growing number of organisations who are trying to make this issues known and proximate to incite change, change of the system and point of views. For example, the campaigns against sweatshops and production of designer or global brands (Allen, 2008). Using the media and communication technology these campaigns can gather momentum, support and more. These campaigns are centred around taking action, and this is accomplished by calling to people’s conscience. Campaigners aim to mobilise the consumers of goods and boycott brands. This is not new, such as boycotting South African food exports during Apartheid and boycotting goods of slave labour by the Women Anti-Slavery League.

A world in the making is particularly true the way we make sense of the world and for empowering people to make a difference. It is for this reason many social movements are collaborating to organise a globalised world. This includes challenging the ‘free trade’ and market forces that dominate currently and ultimately reduce inequality.

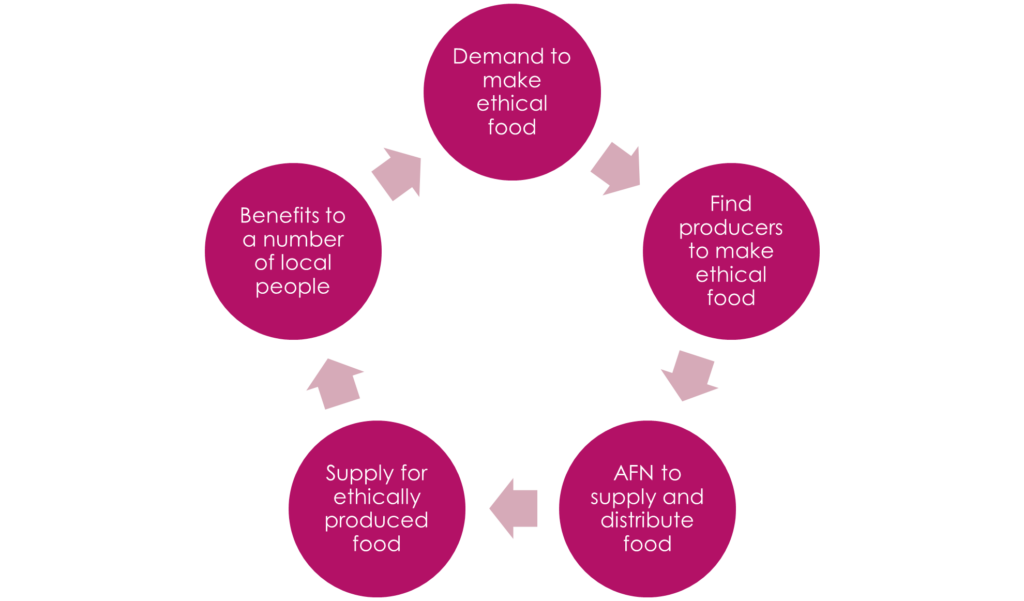

Alternative food networks (AFNs) aim to reduce the inequality of farming and promote sustainable farming practises. They are an organised flow of food products which help those who want to consume ethically produced food and to benefit those who produce it. Ethical connections between consumers and producers, including the social and environmental conditions in which the foodstuffs are produced, are fashioned between an interplay between the flow and territorialisation.

AFNs are defined by the non-conventional food production and trading practises, as well as remaking global markets differently. Articulating the ethical connections between the producer and consumer is but one way people can choose to consume ethically and benefit small scale farmers. However, who is responsible for ethical food production? It is not just the consumer’s responsibility to help other humans, but also non-humans and the environment. Ethical consumption is a small act someone can take to participate.

Food production is important in the dispersal of plant and animal life, but food production is dominated by an economic system. The aim of maximising profit and increasing output has a profound impact on the people producing the goods and the environment that supports them. it also means that only quick, profitable plants and animals are produced.

Food and Global Markets

Food is mass produced in this globalised world often at the expense of the people, animals and environment. Inequality is embedded into the flow of goods, such as one nation importing more as its nation is not self-sufficient and others not being able to grow food due to tariffs and quotas. The setting up of AFNs aims to challenge the current network and chain of food production.

Consumption generally refers to the activities of both provisioning and eating.in highly urbanised areas where production is limited, they rely on rural areas and other nations to produce food – this is a market transaction or flow. Eating and food consumption is socially conditioned to be in one’s home or places structured for consumption like cafes, restaurants and so forth. These facilities built for food consumption highlight the world of plenty and lack of food scarcity.

Understanding how markets work ties a lot into how items are consumed and where, and many regard the process of production to consumption as a straight road. The economic accounts consider the rise of large global players and institutions which organise the production and distribution of goods and services. Consumption can be used to change market forces for good if ethically produced. Likewise, food scares can implicate certain foodstuffs like Bird Flu. Foot and Mouth Disease and so forth. Some of these diseases made worse by the close quarter farming methods and mechanisms. The relative mundane and small actions to demand ethically produced foods can become an action or change and solidarity.

Actions and sourcing ethically produced food is often in response to controversies that have come to light, such as disease, horrific conditions of animal farming as well as highlighting the conditions of farmers themselves. Missions by corporations to deliver ethically sourced food is also now a good selling point for them due to the controversy. Government health agencies and campaigns also seek to promote certain types of consumption, which are in part affected by charitable campaigns and pressure groups.

AFNs are a response to mobilise consumer buying power in pursuit of ethical agendas. Without AFNs people would not be able to wield their consumer power and consume ethically produced goods.

The free market and globalised food trade

AFNs position themselves against the practises of mainstream or conventional food markets. Food, like many other global commodities, are the product of highly industrialised systems of production. It is stuck between;

- Activities associated with the production of goods, like chemicals like pesticides and fertilisers, growth hormones, artificial insemination of livestock, genetic modification and growth hormones. All this to increase the output of farming and ensuring consistent crop.

- Activities associated with food processing, retailing and distribution, like preservatives, radiation treatments, homogenisation, ‘cool-chain’ delivery systems, branding, packaging and marketing.

These activities are more profitable then farming itself and are concentrated to a handful of MNCs. However, despite this, farming itself is still dispersed and underfunded. These are often worked by local people and their families. The price we pay for goods therefore is unequally distributed between the key players and the producers of good see the small margin for their work. This is referred to as the ‘agri-food’ chain involving several parties to deliver the goods.

One of the core characteristics of mainstream production that AFNs seek to challenge is the distribution of costs and profits between the parties. Understandably the MNCs profiteer and farmers do not. As a result, many farmers live under the poverty line and have to work to survive.

The prevailing terms of trade in global food markets centre around the rhetoric of free trade and their practise of imposing tariffs and indeed quotas to not disrupt the status quo of food production and prices. Free trade relates to the freedom of movement of goods and services which is promoted by wealthier nations and international organisations. The breakdown of territories and borders works in removing the expenditure of taxes and tariffs imposed on nations to export and import. It is one part of the neo-liberal aim to reorganise the economy.

The territorial openness, unboundedness and unlimited flows implied by the principle of free trade reveals its limits. In the same way people are denied access to migrate even though there is freedom of movement. This contradicts the principle of freedom. To further this the ‘free flow’ in the global economy is regulated and selective in setting up trading tariffs. Tariffs are a duty or tax added to imported goods to raise revenue and decrease competitiveness of imports in relation to home grown goods. The practise to increase tariffs is a means for nation states to protect their national interests and producers.

Due to the relative advantage of Southern nations in producing food cheaply due to the climate, foodstuffs are particularly common target for imposing tariffs. Protection by tariffs is supplemented by the subsidisation policies for local producers. This helps them from market conditions and tip the terms of trade in their national favour. A combination of subsidy and protection and give producers in the North an advantage over non-subsidised and unprotected producers. This allows the North to export against the tide of lower production costs which otherwise give the South an advantage. This then results in a flooding of the markets of these countries with cheap produce, undercutting local producers.

The system therefore is not open and grossly unequal. Global food market is skewed against the Southern producers and produce of relatively poorer nations. Inequalities are embedded in flows of trade in foodstuffs and territorial practises of regulating flows. The way flows are structured is manifested in territorial effects of food markets, namely reinforcing economic inequalities between North and South. There are tensions between the principle of tree trade and the practise of tariffs and subsidies which impact free trade.

Campaigners go against therefore free trade and want trade justice which affords poorer countries the right to impose their own forms of trade protection. Territories need to maintain control of their own borders and flows through them. The term ‘justice’ implies that flows are levelled, and that flows should continue, but suggests a change in these flows.

However, other campaigners believe that free trade should be pursued properly and tariffs and subsidies should be done away with altogether. This means breaking down territorial boundaries in favour of unimpeded flows.

Subsidies are concentrated in the relatively rich countries that are members of the Organisation of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) with particularly high levels of subsidies paid to farmers in Japan, Norway, the EU and Switzerland. To further this there are a particularly high number of import tariffs are being imposed by the EU, USA and Canada. Areas with no data at all have very low protection for producers, both in tariffs and subsidies. These nations would be the most impacted from this unequal terms of trade – including undercutting by imported subsidised products and barriers to their own exports.

Fairtrade: consuming with a social conscience

AFNs have developed to address the global injustices and inequality in food production. Ethical food consumption expresses a sense of responsibility to distant others, i.e. the producers in poorer countries.

Fairtrade Coffee

Coffee is a global drink, fuelling all manner of social situations, relationships and interactions in this modern day. Coffee is derived from plants native to tropical and sub-tropical climates. Coffee is produced largely in Asia, the Caribbean and Africa which have strong colonial ties and links which have played a great part in its production. The global markets on coffee production have three main characteristics;

- Production is primarily in plantations, with large areas of land owned by a handful and worked on by low paid workers. Labourers are often dependent on the land owner for housing too.

- Plantations replace the mixed ecology of the land with one commercial crop, losing biodiversity and promoting monoculture. This relies on intensive farming strategies and treatments to sustain fertility and control disease.

- The price of these primary agricultural products commodities is unprotected on world markets because they are generally produced in Southern countries. This means that these products can have dramatic price fluctuations. This can occur from climatic changes that impact production or simply disease that can eradicate crop.

MNCs have played a big role as well in determining stock value.

Fairtrade coffee is the only sector of the coffee market that has grown over the last decade, against the overall decline in world coffee consumption. Europe is the largest market of Fairtrade coffee. The Fairtrade movement began as a dispersed set of initiatives by charitable and non-profit organisations in different countries, primarily Europe. Coffee was one of the first commodities to be targeted by these groups. These groups purchased goods from the South for more than they would get on the conventional market and selling to consumers at a higher price than the conventional system. This challenged the current system and aimed to generate an ethical premium which redistributes the wealth.

Ethical consuming did not simply come about through spontaneous action, it requires flows and connection to the South and producers. The AFN developed these ties between the North and South. In the name of globalisation and forging a new form of globalisation, is by forging new networks which link ethically motivated consumers to alternative food networkers.

The ability to act at a distance, where you impact other places and people in the world. Whether Fair Trade or an MNCs must work at fashioning global food markets, and where Fairtrade of environmentally conscious people are concerned, also helps with the socio-economic conditions. AFNs also, like MNCs must advertise and encourage people to purchase their goods above others.

Certification and Fairtrade Mark

An important aspect of taking responsibility for others in a globalised world is to challenge the assumption that the market exchange processes are or ought to be untraceable. However, AFNs success is due in part by directly linking to the producers of their goods and also highlighting the inequality and unfair practises of the conventional system. Drawing these links is important for setting up alternative, ethically motivated networks.

One of the biggest challenges for AFNs is the multitude of ties and links and building something credible regardless of the distances travelled from producer to consumer. Whereas a MNC may want to disguise these connections to avoid taking responsibility, AFNs want to highlight their connections. The journey from producer to consumer can be quite long, such as freeze drying beans.

AFNs build trust through two strategies;

- Product traceability – it is being able to trace where food comes from. It is also making this trail visible and known by consumers. This guarantees fairness of conditions under which coffee has been produced and is vital for ethical farming. In the case of animal farming, meticulous records are kept so producers and consumers know where the meat came from and which herd in case there are any issues. New tagging protocols are needed to ensure a foods clean passage through transportation and processing. This means that ethical claims remain undiluted.

- Ethical credentials – this includes certificates or logos that mean the produce has been made under fair conditions. This makes products easy to recognise and builds customer trust. This also means the development of labour intensive certification process to justify the credentials and raising standards. It involves establishing contractual codes od standards which set standards and reinforced by checks and inspections.

In the case of Fairtrade coffee, certification is signalled by the Fairtrade logo and was consolidated after various efforts and initiatives. Fairtrade Labelling Organisations International in the 1990s agreed on what was considered Fairtrade and adopted a single, international logo. Today over 250 different products are bought and sold in the name of Fairtrade, including food and non-food products. In the 1970s various UK charitable organisations like Oxfam, Traidcraft and others set up the Fairtrade Foundation to administer the Fairtrade logo as their common logo.

The Fairtrade Foundation applies this guarantee by setting and monitoring two sets of generic standards, one for small farmers and one for workers on plantations. The former applies to smallholders organised in cooperatives or other organisations with a democratic structure. The latter is employees or waged workers who are required to pay decent wages and guarantee the right to join trade unions and provide good shelter.

Fairtrade standards stipulate that traders must;

- Pay a price to producers that covers the cost of sustainable living and production

- Pay a premium that producers can invest in development

- Make partial advance payments when requested by producers

- Sign contracts that allow for long term panning and sustainable production practises

The Fairtrade logo invokes the same level of trust and relationship, as well as same quality, as other recognisable brands, such as Nike. Logos are a form of territorialisation, making a mark and enclosing certain things. Hi creates a border for it as it clearing defines and differentiates itself.

Fairtrade logos stabilises a particular set of social and technical arrangements which strengthens the flow of products and reliability of sourcing ethically produced food. The Fairtrade Foundation goes one further and goes considerable lengths to regulate the use of the logo, including manuals on how it is displayed and reproduced on packaging.

Cafedirect: a Fairtrade coffee network

Cafedirect coffee was the second fair trade product to receive the mark. In the UK and is now the top selling brand in the fair-trade coffee market in the UK. It was originally a consortium that grew from informal cooperation between the trading arms of four non-profit organisations which have been the longest serving in the Trade justice movement in the UK, Oxfam Trading, Twin Trading, Traidcraft and Equal Exchange. Before these organisations engaged independently and what constitutes as fair trade, negotiating contracts with coffee producers, monitoring compliance and selling fair trade through a network of charity shops. In 12993 this changed with the consortium registration as a private non-profit company with the casting of a Managing Director and stakeholders.

The reorganisation marks a significant shift in the stability and reach of AFNs, where coffee became the ethical medium of connectivity between consumers in the UK and primary producers in Latin America.

Firstly, the practise of contract negotiations and compliance monitoring with producer organisations dealing with Cafedirect have become more standardised under the rubric of the Fairtrade mark, administered by the Fairtrade Foundation.

This enables Cafedirect’s capacity to deal with larger number of varied producers and complex forms of organisations. Cafedirect can now have different types of coffee and blends as well and marketed according to colour, strength and more with reference to their country of origin.

Cafedirect as well can now sell to a mainstream audience and food retail outlets, which increases their market. In the 1990s they marketed their ethical associations and used a tagline of the aroma of fresh coffee without exploitation.

Today much of the work of differentiating Fairtrade from mainstream products is done by the logo itself. The primary imagery used on advertising is concerned with where the coffee or other items were produced. Determining where products come from is a tool often employed by Fairtrade producers to engage with consumers. Fairtrade producers also go one further and demonstrate the benefit of purchasing Fairtrade goods, like trade justice.

Combining third person information with first person accounts, whilst also employing photographs, is one way campaigners enrol people in changing a globalised world (Rose, 2008). Developing emotional attachments is a powerful part in rallying support for a cause, and trade justice stories do just this.

Building an emotive link also constructs consumption as more than just an activity, we are drawn to identify or be in solidarity with other people across the world by building meaningful links. Unlike the internet however, food consumption is one-way communication. We see the producers but they do not see the consumers. Likewise it helps establish a role and responsibility, that people of the North have to consume ethically and people of the South have to work and innovate – both groups remaking the global world.

To further this, the internet and webpages surrounding Fairtrade not only try to be informative but encourage you also to participate. There are many prompts on the website to get involved. There are invitations to get involved in the Trade Justice Movement as well as expanding fair trade practises and certifications to institutions, towns and groups.

Fairtrade is also supporting sustainable farming methods to benefit the environment and improve the quality of life. As demonstrated in farming, the environment and human life are deeply entangled.

Organic food: more than human ethical concerns

Through territorialisation, responsibilities towards others are articulated through the global market, and goods are mobilised to make a difference in the world. The question of responsibilities and ethics of consumption can be posed differently if asked what are ethical connections made of?

Ethical connections are realised and exposed in how human wellbeing and non-human treatment during and after food production is intimately connected. These connections are shown in food scares when humans are impacted by food safety and wellbeing – such as Mad Cow Disease (1990s) where a degenerative brain disease was being passed on from infected cows to humans (Ridley and Baker, 1998).

The interplay between the spatial practises of territorialisation and flow that shape global food markets is through the intimate design of the food industry. Some AFNs are not only concerned with the consequences of intensive farming methods on human health and animal welfare, but also how we promote unsustainable and environmentally degrading methods and we should take this responsibility when producing and importing these goods.

Intensive farming methods although increase the output of food and food production, often at the same standard. However, this has come at a cost to animal welfare and environmental degradation.

Intensive Chicken Farming in the UK

- There are approximately 29 million egg laying hens

- Over 70% are in battery cages

- Most battery cages house four or five chickens to save space

- Most battery cages are no more than the size of an A4 piece of paper

- At this proximity disease is common

- Birds suffer stress and act aggressively

- Beak trimming, wing clipping and incorporating antibiotics in diets to prevent damage and disease

- Birds are often kept in dark conditions

- It is estimated some 100000 chickens die every day prematurely

- It has had consequences on human health like salmonella, food poisoning and other bacterial infections from the farming conditions

Historically chickens have been reared for consumption for centauries and they are engrained in most people’s lives, whether rich or poor. In recent times chickens, have been split into laying birds or broiler birds and because of this selection, particular characteristics have been harnessed and bred into these breeds. The quality of life for chickens has been tailored to make production efficient, including life span, feeding and other characteristics.

In time bird production, has become more concentrated to space and breeders and in the 1950s only5% of laying were kept in flocks of over 1000 birds. By 1995 this was 95% of birds. The largest farm in today’s standards has about 500000 birds.

Many campaigners have been involved in fighting for animal welfare in meat production and conventional market practises. The RSPCA is one organisation concerned with eradicating animal cruelty. Campaigners have also been concerned with environmentally degrading farming practises that have damaged the environment in meat production. Soil Association is concerned with improving conventional farming practises and is a leading player in the organic food movement.

Where egg and meat production is concerned, there are a variety of standards and certifications. This makes it difficult for AFNs to address the concerns over animal and environmental welfare, as well as making consumer choices difficult.

Setting animal welfare standards

It is a minefield of regulations and accompanying logos and it is difficult to know how ethically the products were produced. All eggs in the UK must follow UK and EU legislation and compliance with these rules. That is there are minimum standards that farmers must reach to produce and sell. There are trading standard authorities to enforce these standards by checking production. This demonstrates the long-standing concerns over meat production on human health. However, battery hen eggs still meet the minimum requirements and the stamps and logos only certify that much. These standards and logos therefore demonstrate that goods are not always produced ethically even though they are certified.

The Bramwell Committee (1965)

They set the baseline definition of what constitutes farm animal welfare in the UK and makes the Bramwell Five Freedoms. It sets recommendations on animal welfare standards on farm welfare in 1979.

- Freedom from hunger and thirst with ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health

- Freedom from discomfort by providing appropriate environment including resting and shelter

- Freedom from pain, injury or disease by prevention of disease and rapid diagnosis and treatment

- Freedom to express normal behaviour with proper facilities, space and company to the animals own kind

- Freedom from fear and distress by ensuring conditions and treatment avoid mental suffering

These are recommended codes and not legally enforceable, but over the years and in response to demands to improve animal welfare, these codes have been translated into legislation. These standards and legislation is a form of territorialisation which aims to impose limits on the territorialisation of animal bodies and welfare. The freedom to express normal behaviour acknowledges that the territorialisation of industrialised livestock constitutes an acceptably restrictive channelling of flow of non-human life and their behaviour.

The claims from AFNs are less distinguishable from conventional food networks by the practise of territorialisation – standards, logos, etc. AFN has to work harder to differentiate the reliability of their trading mark and act as a demonstration they have more rigorous standards. These standards also could appeal to consumers as well as the rigorous standards includes air quality, herd density and many other aspects of food production.

The RSPCA launched it Freedom Foods trademark backed by an inspection and monitoring regime to promote higher welfare standards. Freedom Foods highlighted as the monetary value of goods also has an impact on the conditions for which animals were raised. The cheaper the goods the poorer the conditions. This was a campaign to try to alter thinking and promote animal welfare. However, the trademark has been criticised for its low standards and retains some controversial tactics like beak trimming.

Nevertheless, the trademark gains the highest number of first places for different categories, like laying hens conditions. The Soil Association also has come up with its own standard for organic production. 150 million eggs produced by some 700000 chickens comprises of the UK organic market. The Soil Association is distinctive compared to other organic products as it does not depend on imports, but is entirely derived from local producers.

Niche market or force for change?

Ethical consumption while taking advantage of markets, can also operate as a force which challenges the way that global markets can also operate as a force which challenges the way current global markets operate.

Ethical consumption is one act of participation. However, some argue Fairtrade and organic products are only for a niche market. The logic behind this is due to the expense of the pricier Fairtrade goods which would only be afforded by wealthier people, ultimately limiting their market. Sparing the expense on Fairtrade goods seemingly saving the conscience of the consumers, where ethical consumption is a substitute for active campaigning. To further this, as some producers become more successful the ethical credentials of the AFN become diluted as they work with MNCs and the mainstream food market.

Research into this consumption shows that if people had a choice they would opt for organic or Freetrade foodstuff, regardless of cost. This research was conducted in Europe which is a largely wealthier nation. It seems people were prepared to spend extra of their pay cheque towards ethical farming. The claim AFNs become mainstream is very complex, and as businesses grow they are expected to increase suppliers and distributors. AFNs would use several outlets, and not very often supermarkets which promote the current conventional system of food production. The capacity of AFNs to work with and influence mainstream institutions and networks can be regarded as undermining MNC expensive charges and elitism and instead the successful promotion of their message.

Because of the success of Fairtrade goods, MNCs are looking to make their own brands more ethical in production and challenge the Fairtrade wave. Kraft which owns Kenco, Carte Noire and other coffee brands is beginning to introduce sustainably produced coffee in many of its brands. These have been certified by the Rainforest Alliance which certifies sustainable production both socially and ecologically. However, all these certifications and standards pose problems with consumers.

The development of collective initiatives as well demonstrates the expanding uptake or mainstreaming of trade practises. Fairtrade regions and the conversion of institutes like universities to Fairtrade goods is one way people are wanting to adopt Fairtrade goods. The House of Commons and the AMT coffee outlet is one way outlets are adopting Fairtrade foodstuffs. The adoption of Fairtrade can affect society more broadly and may cause a domino effect with more people demanding the adoption of Fairtrade.

AFNs are gradually changing the view of what is publicly acceptable and ethical standards. It may cause even greater shifts of global sourcing protocols, not just for people but MNCs as well. McDonalds is one such example where an MNC which previously exploited animals and welfare now promotes sustainability and welfare in order to attain trust which consumers and they are a marketing ploy. AFNs promoting animal welfare foods are quick to highlight how bigger cages is still factory farming.

Buying Faritrade however is not enough to bring out change in the global food trade. Ethical consumption is the first step and can lead to other forms of participation. Consumers can be mobilised for more ambitious projects other then changing their consumer habits.

An example of mobilising people to change the system was in 2000. A group of Oxfam activists in Garstang announced their town was the first Fairtrade town in the world. The Fairtrade Foundation then seized the campaign and formalised into a national campaign. By Fairtrade Fortnight in 2005, 100 towns and cities in the UK were awarded Fairtrade Town or City and a further 200 were awaiting approval.

As well as encouraging consumers to back Fairtrade town and cities initiative, people are also encouraged to promote the Trade Justice Movement. This is abroad alliance of organisations including Oxfam to transform the organisation of international trade in the interest of trade and justice. As well as preventing environmental degradation, that is occurring in the South.

The Trade Justice Movement has also joined the Make Poverty History campaign which drew some 225000 protestors to Edinburgh in 2005 to demand trade justice, debt cancellation and increased aid for the world’s poorest nations from the leaders of the wealthiest nations (gathered at the G8). Meanwhile Caredirect was serving Fairtrade coffee to the world leaders.

Global solidarity for local agriculture

Ethical consumption can open many other forms of solidarity, beyond consumption. By establishing new connections between producers and consumers, much AFNs consider themselves as part of a broader movement. This movement is to not only change what we eat but where it is produced. International organisations seek to transform agriculture and promote sustainable globalisation, bridging the gap between North and South.

Like the attack on malbouffe (bad food) shows, Via Campesina advocates the right of agricultural producers to have a degree of protection with regards to food standards. It is about getting fair prices for their produce and not having local or national markets distorted by the neo-liberal market. This neo-liberalism forbids consideration of the ethical origin of traded foodstuffs.

However, it is also the defence of the uniqueness of local production in the face of growing homogenisation as a result of neo-liberal globalisation. Malbouffe is inherently unhealthy and is derived from the intensive, industrialised farming methods. Food during consumption is standardised and uniform, and abnormalities are removed regarded as unclean or unhealthy. Much of our understanding of good food comes from local knowledge and embodies traditions.

Ethically food by contrast promotes the abnormalities and uniqueness that comes with unconventional farming production. AFNs critique malbouffe and industrialised farming methods as they are not regarded as ethical or healthy. AFNs therefore connect good producers with good consumers or consumers wanting to eat healthier and ethically. Due to the promotion of SME farmers and non-conventional (and less intensive farming) means that AFNs support place, locality and community (territory). This call to defend territory is amongst the calls for greater flows.

In this context defending place or territory is not closed or bounded, but seeks to regulate flows which nourish the environment, like trade of good food which benefits the community and environment. Campaigners are not opposed to globalisation and flows as such, rather maintaining flows to ensure good practises are upheld and local works valued. It challenges the current nature of flows.

Local areas and temperatures give rise to diversity and uniqueness for many areas. Different places have different native plants, traditions, breeds and more and globalisation and growing homogeneity threaten diversity. Rural life is composed of a weave of connections, local knowledge, farming traditions and food specialities and deep entanglement with the environment and human life. Within this it is not saying good food and local traditions should not move freely, but neither should they be threatened.

Trade justice and animal welfare are but two parts of ethical consumption and a way of challenging conventional, intensive farming practises. AFNs aim to build networks and source not only good food, but food that benefits the producers and the environment. It demonstrates the deep entanglement between the human and non-human and how the way we treat producers impacts the consumer, such as disease, market value, etc. although farming practises and understanding have changed over time, they retain significant elements of their own force and integrity.

Small farmers and those that promote sustainable farming methods have been the guardians of genetic diversity and retention. Animals and crops play an important role in biological diversity and as part of the human interest to survive, many new species and diversities have arisen. Farming practises and cultivation directly impact the environment and decisions they make can enhance or degrade the environment. Organic processes which respect natural soil processes can promote biodiversity and preserve or restore biological fertility (Soil Association argues).

Participation in AFNs and ethical farming through consumption benefits the richness and diversity of soils and territories. It can benefit soil degradation over significant number of years as well. Therefore, distance and time can be affected by participation.

In 2003 the Soil Association and Fairtrade Foundation announced a new agreement about ways of collaborating. This included a proposal to work closely together and improve the speed and ease of certification for producers in the developing world who wish to sell products that are both Fairtrade and organic.

From Alternative Food Networks (AFNs) to new global architectures

People are mobilising around the world into order protect local sovereignty of territories and to win them the right to protect their own practises and environment. The integrity of the local community and products should not be taken for granted, and these are made, not preordained. In an increasingly globalised world the integrity of places and people needs to be worked at. Understanding the interplay between territories and flows is important in understanding that global solidarity is necessary to protect the local.

What is the integrity of the local in the globalised world?

It does not mean the closure of borders or the local against the outside world, or rejection of change. Simply a challenge of the connections and flows that currently exist and benefit the few that needs to be remade.

Spatial form is not in itself good or bad, i.e. local is better or worse than the global as though they are mutually exclusive. There are powerful local places as there are powerful global spaces. The claim for local control by local people will have a different force and meaning in different situations.

AFNs and the movements to benefit local people and those less fortunate highlight that international trade regulations, like tariffs and subsidies, damage and limit production. As this is challenging the local architecture, the architecture needs to change also. AFNs therefore needs to remake the architecture and know what works and what does not – ethical trading and consumption as a systematic solution confronts the question of what is territory and flow and how can sustainable practises increase. AFNs and organisations aim to mobilise consumers in support for changing the ways the markets work and making emotive links.

Existing architectures organise territorialisation and flows of goods, and a new architecture challenges this. It also challenges the relationship between people and groups, as well as their relationship with the non-human world. The global architecture almost ignores local knowledge and understanding of the local area, and this has consequences. The global architecture needs to understand the irregularities and inconsistences not only with local land and soil, but also in regulations and laws which regulate them. Activities from both humans and the non-human from millennia have helped shape the landscape, soil diversity and built understanding of the local land. To further this plants and animals have adapted to the land as well.

The neo-liberal dogma dictates that agricultural markets are self-regulating but this is not true when considering they are dependent upon the crop, the conditions and more. Although demand is stable currently, it is susceptible to climatic changes, and this impacts production and consumers. Most nations have policies to regulate supply to meet demand, as well as determining local supply and ability to import. A world market is unable to provide the necessary regulation some argue.

Human activities are impacting the climate further and making it unpredictable, which impacts the flow of food and impacts consumption. Quick changes will impact local knowledge as well which has been built up over the years, and there is a great need for understanding local knowledge. Variability and unevenness is more important when considering Climate Change will threaten the way of life.

To further this soil fertility and care is also important in reducing carbon emissions, and the right soil can act as sinks much like forests can. Restoring the productivity of degraded soil a consequence of intensive farming, ism important in mitigating the impacts of Climate Change (IPCC).

The global architectures which are put in place to organise the flows and territorialisation’s of human economic activities have immense implications for the flows and territorialisation’s of the non-human world. Farming for food is the most historic ways humans have controlled the flows and reorganised the territories of plants. Human have dominion over the land and humans, sufficing their own interests, impose controls on behaviour and the form of organisms. The welfare of plants and animals therefore is at the expense of farming and ignored in intensive farming. This imposing for controls, like rules and regulations, mean that such creatures are unable to flourish and express themselves. The challenge to the current architecture which is built on increasing output through exploitation and disregard for welfare or the environment also challenges the power structure – humans are better the non-humans and the wealthier nations exploit the poorer nations.

The question of restructuring food trade and production relates to the issue of territories and flows of biological life, including plants, soil, air and more and how food production depends on this. The issue of transforming architectures of food production and trade in an increasingly globalised world requires us to think of the global implications of localised or place bound activities. What makes good food is brought into question, and how much is human responsibility for sustaining physical system (of the local land and global climate). This is important for both human and non-human life to flourish.

Conclusively, shopping for food is part of making a globalised world. Changing the habits of consumption and what we eat can have an impact on distant lives both human and non-human, like biological life and the environment. Our eating habits contribute to the making and remaking of the world and territories, as ethical consumer and producers highlight.

Changing Consumption

By supplying an alternative food supply which has been produced non-conventionally it has meant consumers can easily contribute to sustainable development and food production. It also tries to eradicate the complicated lines of manufacturing and means people can take greater responsibility for development. The act of consumption can involve people in larger movements for change. Small acts of ethical consumption can become larger movements, like Freetrade institutions and help collective efforts to transform the world. However, ethical consumption is not possible without using current forms of manufacturing and distributing.

Consumption brings attention to the fact we are no more responsible for what happens in our own country then it does for other countries (Young, 2003). Our food networks also concern the environment and non-human life, so our responsibilities extend beyond our own place. This is true for considering animal welfare, human welfare, environmental concerns and food production somewhere else in the world. Calls to eat well and differently embody a challenge to power relations that structure our interactions with the human and non-human.

Architectures that organise global trade in foodstuffs have important implications for the flow and territorialisation of wealth and economic opportunity within groups. These structures also impact on the flow and territorialisation of animals flows, bodies and behaviour.

AFNs are one way people are trying to restructure the world, and showing how we can order the world differently.