Most of the modern medicines we ingest today, like Aspirin, have come as a result of ancient medicines, nomadic civilisations and colonisation. The World Wars advance medicines and their creation, which, were a result of experimentation and ancient remedies.

New finds rely on science and its advancements, knowledge and the proliferation of it and the ability to experiment.

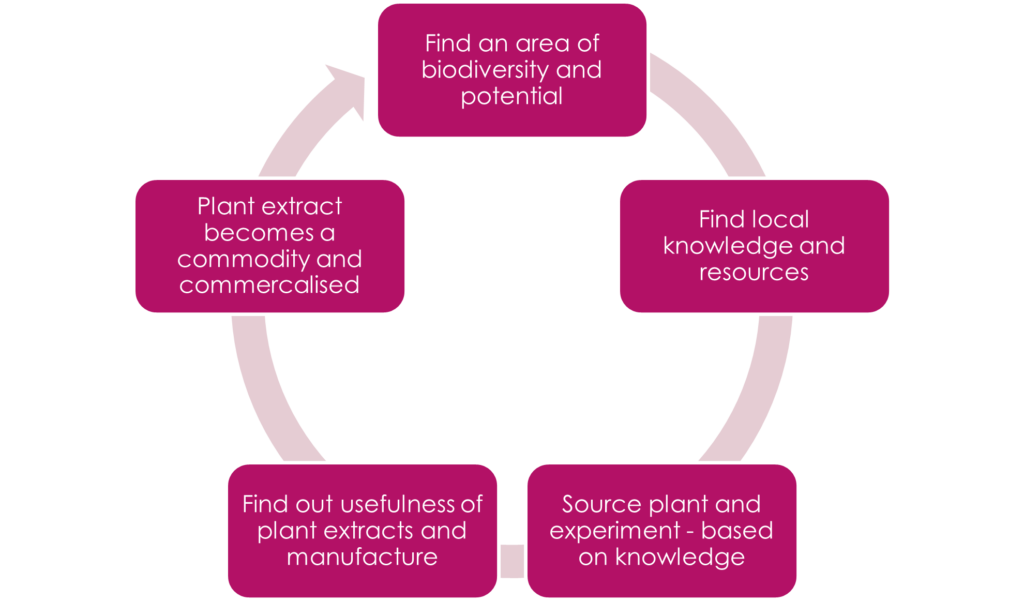

The entanglement of the politics and knowledge of making and creating remedies is referred to as bioprospecting, which involves the knowledge, sourcing of plants and the large pharmaceuticals which recreate these materials.

People and plants: a globalising relationship

Unlike animals or humans, plants cannot move from their attackers or extend their reach without help. In the absence of being able to move, plants have to rely on evolution to survive. Plants are impressive in that they can transform water, sunlight and soil to manufacture resources that sustain us, including medicines.

The chemicals plants produce is often for defence, to compel creatures to leave them alone, whether through bad smells or poison. However, some substances are to attract creatures necessary for reproduction or spreading their offspring. Attraction also made humans and animals alike their servant, to get rid of their predators and to cultivate them, perhaps for medicine, or taste or beauty.

Humans and animals rely on plants for their everyday life, like food, shelter, clothing, transport and more. The relationships between humans and plants is often stronger when comparing indigenous tribes and their environment (which they have occupied for years) and do not manufacture the plants in an industrial fashion.

Plants and vegetation also regulate the atmosphere, providing valuable oxygen and regulating the climate.

Michael Pollan, 2002

Explores the various ways plant life has migrated and globalised the world. About 100 million years ago Angiosperms came in to existence, species of flowering plants which are seed-bearing vascular plants. They are the most diverse group of land plants, with 416 families. The seeds were intended to be eaten and disseminated elsewhere.

Then about 10000 years ago a second coming of diversity came about through the invention of agriculture. The plants used species to move them, nurture them and destroy its predators. Edible grasses like wheat and corn incited humans to cut down forests and grow them. The relationship between plants and people is deeply entangled, and the immobility and biochemistry of plants plays a vital role in globalisation.

Ethnobotany is the study of interactions between people and plants. It focuses on the different ways in which individuals and groups and incorporated plants into their lives, and how plants are the material basis of human culture. The peoples Earth has much relied on the plants. Without plants regulating the atmosphere and providing food and energy, we would not exist.

Balick and Cox (1996)

Are ethnobotanists who explore how plants use indigenous people who follow traditional and non-industrial lifestyles, in areas occupied for generations. This is because the relationship between plants and indigenous people is easier to distinguish, i.e. the link between production and consumption.

The depth of entanglement is evident in the fact humans have superseded all other mechanisms as a migratory body for plants, dispersing their seeds. Before this it would have been the wind and wave currents, as well as using birds and other migratory animals.

Plate tectonics and Climate Change have played a role in the spread of plants also, i.e. plate movements have made proximate or distanced land masses, bring plants closer or further apart. Plants exist in some regions due to a change in temperature and then evolution with newer temperatures, like relict flora in the European While Elm in Western Siberia.

The migration of plants

The migration of plants by human intervention is often deliberate, like moving sugar cane, wheat and rubber to new markets. Looking throughout time most of these plants originate outside Europe and are imported in. The nations of Europe have benefitted from the transfer of useful plants. This is particularly important during the 15th and 20th centuries when nations were being built and required resources. Territories and flows play a large role in the globalisation of flows and flora. Flows both make and sustain territories, and this is no different with plant life.

Kew Gardens in London was one way to demonstrate imperialism and the various flows. It was built in 1844 – 48 to house tropical flora bought back from the Empire. This was to showcase wealth, novelty and more.

The Wardian case made travel of the plants from the tropics and the Empires possible, it was like a transportable greenhouse which protected plants from the dangerous elements like ocean winds and rain while travelling. This device was critical to the survival of and the migration of plants, which, could sustain life faraway. While the flow is apparent, the territory is less so.

It can be argued that plants are territories themselves, and indeed without plants, territories cannot form. Entangled flora and fauna life make territories emerge.

The flows of a plant

Physical flows

Humans have physically transported plants to various areas for various reasons, sustenance, shelter, medicine and more. This is physical flow of plants from A to B

Anatomical flows

Plants possess anatomical flows within them, converting carbon dioxide and water into a range of essentials like oxygen, medicine and more

Making territories

Boundaries are drawn in a variety of ways, and borders define boundaries and what is contained and left out. Territories are defined and differentiated from the surroundings. Plants have a role in defining some boundaries, especially if flora occupies some regions. Flora as we have said cannot move as easily or as rapidly as say moving animals or humans (fauna).

The Wardian case is an example of a change in territories, like with imperialism, as flora can move – albeit not autonomously. The Wardian case can uproot plants, both literally and metaphorically, and can cut off the connection which would normally define existence. In order for something to flow easily, it cannot be attached to an object or land mass.

Bronwyn Parry (2004)

Globalisation determines the social and spatial dynamics of flows. Groups have the ability to access, acquire, harvest and monopolise goods. The process of sourcing goods, harvesting and then taking create the have and have nots. Bioprospecting, which is the search for species from which medicinal drugs and other commercially valuable compounds can be obtained, is causing the globalisation of plants.

Economic, technical and legal developments, are providing opportunities for the ‘territorialisation’ of plants, and opening new doors for flows and access. Such developments can make territories, and distinguish others. Some groups are more willing to access and source botanical medicines for their gain and profit. Some groups have more power than others to source botanical medicines, and now bioprospecting is heavily politicalised. This has exacerbated tensions, and deepened the lines of inequality.

Making bioprospecting profitable

Since the 1980s the world saw a global effort to accumulate biological matter, and it mirrors the effort in the Empire age. Between 1985 and 1995 it was estimated that 200 US organisations began new biological collection programmes,

Biodiversity plays a big role in bioprospecting, as it continuously offers new pharmaceutical products. Biodiversity is the diversity and variation amongst species, where new species are discovered every day and with further research can potentially discover cures, which, can be sold at profit.

Influential economists have leveraged biodiversity who seek to both put a value on biodiversity and that neoliberal capitalism, which was responsible for the extinction of species, could also save species.

Free Market Environmentalism (Eckersley, 1993) was the term coined for the profiteering on nature, to save nature they need to sell it. By pricing and privatising nature could result in its conservation. Some nations could be offered a new way to develop, in merchandising their biological assets, which were previously undervalued. Such nations who were economically poor, but biologically diverse, could find a development strategy in conversing nature and selling its diverse resources.

Brundtland Report (1987)

Was a creation from the UN commission into the idea of sustainable development, development which does not impact the future generations in a negative way.

These ideas gained institutional legitimacy and included a much broader audience as it became embedded in the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity. This global architecture organised bioprospecting and made it possible and legitimate.

At this meeting, and its follow ups, it took the view that biodiversity needs to be conserved for its economic value, which is in alliance with biologists, researchers, policy makers and more. Everyone would benefit from conservation, the poorly developed nations and the wealthier ones too.

Since the 1950s most companies dedicated resources to creating synthetic compounds for medicine. This would be to target specific diseases or modifying existing compounds. By the 1980s this shifted to finding cures or new species to modify.

After this there were a series of developments to make plants seem profitable

- Plants play an essential role in healthcare in treatments, ointments and cures. Prescription drugs contain plant extracts or principles from higher plants – at least 119 chemical substances are derived from 90 plant species

- 80% of the worlds inhabitants rely on traditional medicine for primary healthcare (Lewis, Medical Botany)

- New technology which could measure or break up molecules more effectively.

- Slowing innovation – people thought everything had been found out and accomplished.

Professor Walter Lewis of Washington University was awarded a substantial grant to research Peruvian medicinal plant sources for new pharmaceuticals. By the 1990s biodiversity and bioprospecting became fashionable and profitable, and this is how Professor Lewis attained funding.

The International Cooperative Biodiversity Groups (ICBG) had its beginnings in a workshop in Washington in 1991. It was organised by the UN National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the US Agency of International Development (USAID). It was concluded in these workshops that pharmaceuticals derived from tropical regions, could both promote economic growth in developing nations and conserve biological resources.

The CBD provides institutional encouragement to the globalisation of biodiversity and introduced a new requirement, of reciprocity in recognising inequalities and the power of collecting valuable resources. The South would therefore continue to supply resources in exchange of compensation, technology and more from the North – although this was contested. Of course southern delegations would agree to this agreement, but much to the dismay of the US dominated biotechnology lobby. In the terms of the Convention, the South could not get its way and simply restrict access, even though nation states do how the power to limit interactions.

The global commodification of plant resources came to head when plants were regarded as profitable resources, in exchange for benefits in return for their acquisition. During colonial times it would have been accepted for the North to simply take from the South. During post-colonial times, and with the entanglement of both the biophysical world and the markets which control development and power, plant commodification was the result.

Commodities are defined by:

A raw material which is deemed useful and valuable, which can be bought and sold, such as copper or coffee.

Commodities are

- Items which can be placed in a context where they have exchange value

- They can be disassociated from their producers or former users in order to be sold

Commodification therefore is the first form of territorialisation involved in bioprospecting, making the worlds medicinal plants available for commercial use. This involves a lot of flows, but in order for there to be flows, there must be territories.

The Cycle of Bioprospecting

<!– /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:Wingdings; panose-1:5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0; mso-font-charset:2; mso-generic-font-family:auto; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:0 268435456 0 0 -2147483648 0;} @font-face {font-family:”Cambria Math”; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536869121 1107305727 33554432 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:”Century Gothic”; panose-1:2 11 5 2 2 2 2 2 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:647 0 0 0 159 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:””; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:8.0pt; margin-left:0cm; line-height:130%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} p.MsoListParagraph, li.MsoListParagraph, div.MsoListParagraph {mso-style-priority:34; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:8.0pt; margin-left:36.0pt; mso-add-space:auto; line-height:130%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} p.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpFirst {mso-style-priority:34; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-type:export-only; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:0cm; margin-left:36.0pt; mso-add-space:auto; line-height:130%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} p.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpMiddle {mso-style-priority:34; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-type:export-only; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:0cm; margin-left:36.0pt; mso-add-space:auto; line-height:130%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} p.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, li.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast, div.MsoListParagraphCxSpLast {mso-style-priority:34; mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-type:export-only; margin-top:0cm; margin-right:0cm; margin-bottom:8.0pt; margin-left:36.0pt; mso-add-space:auto; line-height:130%; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.5pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.5pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.5pt; font-family:”Century Gothic”,sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-ascii-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-hansi-font-family:”Century Gothic”; mso-hansi-theme-font:minor-latin; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi; mso-fareast-language:EN-US;} .MsoPapDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; margin-bottom:8.0pt; line-height:130%;} @page WordSection1 {size:612.0pt 792.0pt; margin:72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt 72.0pt; mso-header-margin:36.0pt; mso-footer-margin:36.0pt; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} /* List Definitions */ @list l0 {mso-list-id:611672810; mso-list-type:hybrid; mso-list-template-ids:-461481154 -1825173576 134807555 134807557 134807553 134807555 134807557 134807553 134807555 134807557;} @list l0:level1 {mso-level-start-at:0; mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @list l0:level2 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l0:level3 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} @list l0:level4 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Symbol;} @list l0:level5 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l0:level6 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} @list l0:level7 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Symbol;} @list l0:level8 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l0:level9 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} @list l1 {mso-list-id:662977630; mso-list-type:hybrid; mso-list-template-ids:382624474 -1825173576 134807555 134807557 134807553 134807555 134807557 134807553 134807555 134807557;} @list l1:level1 {mso-level-start-at:0; mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings; mso-fareast-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-fareast-theme-font:minor-fareast; mso-bidi-font-family:”Times New Roman”; mso-bidi-theme-font:minor-bidi;} @list l1:level2 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l1:level3 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} @list l1:level4 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Symbol;} @list l1:level5 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l1:level6 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} @list l1:level7 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Symbol;} @list l1:level8 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:o; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:”Courier New”;} @list l1:level9 {mso-level-number-format:bullet; mso-level-text:; mso-level-tab-stop:none; mso-level-number-position:left; text-indent:-18.0pt; font-family:Wingdings;} ol {margin-bottom:0cm;} ul {margin-bottom:0cm;} –>

Factors which affect Bioprospecting

Legal & Social

Ø Agreements and consent

Ø Social ramifications of the development

Ø Imparting knowledge before it is lost

Financial

Ø Funding for the expedition and testing

Ø Funding for the technology, people and resources

Ø Profiteering from biodiversity (ROI)

Geography

Ø How easy to access is the region?

Ø How easy is it to transport people and technology?

Making bioprospecting practical: territorialisation through technology

Technology has greatly advanced the effectiveness of transporting plants for testing. Before it was physically uprooting a specimen and transporting in a Wardian case to some far off place for further testing. Now with processes like bioassay, moving plants is much easier, not to mention test on. This has undermined the power of nation states ‘owning’ certain things.

Before the economically exploitable jackpot of biodiversity in the 1990s, the Peruvian government was encouraging those who used the land to do so more productively.

The globalised world is made from both humans and non-human components.

Making bioprospecting practical: territorialisation through property

Bioprospecting is a question of ownership and patenting in order to make profits – however who owns what when it comes to biodiversity? Should local knowledge take precedent, or the large pharmaceuticals when it comes to profit making? Does something have to be in a certain state or jurisdiction in order to own it, or it is based on legal agreements, which may have no footing in some nations.

Exclusion is key principle to ownership in Western cultures, i.e. you cannot do this because it is not yours. The concept of property is used to refer to a system of rules governing people’s use of things. Such things can be corporeal like a building or non-corporeal like an idea or thoughts. Property rules are intrinsic in defining ownership and reducing the likelihood of conflict over resources, more so if they are scarce. Property rights are social rights, which are maintained, amended and made within a system of governance.

Ownership relates to territorialisation as it concerns the ability to include and exclude, or bind or alienate a product to its source. Ownership requires that something can be detached from its surroundings and become territorialised in that it has its own border where someone can or cannot access it (with controls in place).

Issues can arise as there is more than one regime of access, usage or control over substances, which can be applied to biodiversity. How can the species of property, i.e. common property, collective property or private property apply to biodiversity?

There are two contested ways in which biodiversity is considered property;

Convention on biological diversity, 1992

States have the sovereign rights over their own biological resources. Therefore, whether resources reside, is owned by the state where it resides. However, states are responsible also for the conservation, protection and nurture of their resources, and to use in a sustainable manner. Biological resources therefore are a collective property.

The CBD was upholding fundamental principles dating back to the 16th century, where sovereign states have a right to permanent sovereignty over their territories, including the natural resources that exist within them. This of course counters the ‘common heritage’ principles which would have leveraged historic ties like imperialism in order to exploit poorer nations, i.e. the richer Western hemisphere exploiting the resource rich and previous states under the Empires. However, the developing and resource rich nations need to increase their funds in order to manage, sustain and profiteer from their biodiversity.

Agreement on Trade related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), 1994

This was administered by the World Trade Organisation (WTO), where the model of private property was favoured, namely patents. Patents are designed to provide inventors to have the legal rights of a product or idea for a fixed period, and to claim royalties from this. It is a means to prevent others from stealing ideas, property in order to sell or import. Patent applicants must satisfy a strict criteria and to justify the uses of their invention, which is described in the application. The idea or product must involve some innovation that exceeds the current state or oblivious to professionals/ skilled practitioners. Patents have been increasingly used in the business industry like private pharmaceutical firms in order to justify the cost for research and development. This thought is highlighted in TRIPS.

The idea that plant materials, or plants themselves, should be privately owned is often contested. Can the concept of private property be extended to living things? This is also a Western model of business being enforced on other cultures, and of course this benefits Western industries and private businesses. Other cultures, like say the indigenous communities in the Amazon rainforest, or the Native Americans in the USA do not believe in ownership or property rights, so how can you impose them?

Issues with patenting and intellectual property;

Ø Communities do not recognise private ownership as they are founded on the concept of individual ownership. This does not suit community based cultures and indigenous knowledge is based on ancestors, deities and more, so these cannot be owned.

Ø It is intended to benefit communities and society through granting permissions and access. However, some communities do not recognise legal personality and cannot claim legal rights to a person, group or organisation.

Ø Information cannot be protected or associated with an individual person or group as knowledge is shared and passed on. Often knowledge is a result of historic discoveries, and is commonly shared, so knowledge is unprotectable.

Ø Conflicts of customary systems of ownership, tenure and access.

Ø Fail to recognise or respect spiritual, cultural or even local economic values.

Ø Subject to manipulation by economic interests that wield the greater political power. Although sui generis (Latin for of its own kind, and used to describe a form of legal protection that exists outside typicallegal protections — that is, something that is unique or different) has been obtained, indigenous people lack the means for protecting their sacred plants, places, artefacts or knowledge.

Ø Most IPR (Intellectual Property Rights) like patenting are expensive, complicated and time consuming to obtain, and even more difficult to defend.

Territorialisation of plant materials is beneficial to private firms, but not necessarily the communities where discoveries were made. The profiteering and exploitation is sustained by a global architecture from the powerful states (located in the Western World) and produce even deeper inequalities.

Khomani & the CSIR

The Khomani, an indigenous to the Kalahari Desert in South Africa, who, eat part of a plant called the Hoodia as an appetite suppressant. It was used for long trips and hunts in order to sustain their appetite. It was noticed by south African soldiers who used the Khomani as trackers during the 1980s during the war of independence for Narambia. The South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), a government institute, investigated the plant. They patented certain compounds and hoped it could be a drug for obesity. However, the Khomani were not mentioned in any reports and were not credited with the find. They were criticised by NGOs and in 2001 initiated a benefit agreement in 2001 which would mean the Khomani would receive payments towards the discovery.

The challenge of territorialism in a globalised world

Globalisation seems to mimic the imperialism in the previous century. It mimics its exploitation of the poor and developing worlds at the profit of other Western nations, whom, have a high involvement in global decisions. Bioprospecting is similar to that of biocolonialism and biopiracy, where richer nations take advantage of the poorer ones who are rich in resources. Exploiting such resources as plant material is similar to that of the imperial period and using examples of the Wardian Case. The benefits the Western World has had from new discoveries and medicine from other nations is uncalculatable, and similar to the Slave Trade, echo the calls for recognition of wrongdoing and compensation.

There are continuities between the plant imperialism of the past and the globalised bioprospecting of today. The practises and processes of the past continue into today. Bioprospecting has arisen for the need to find cures, look into the effects of Climate Change (and look into mitigation) as well as entering new financial markets. New developments have made and re-made territories and this is the same for bioprospecting, where social and special dynamics are changing. This has implications beyond the gathering and usage of resources.

It is easier to territorialise things through technology, finance, commodification and property rights. Being able to territorialise something means it can flow through borders. In international law the nation state has always been sovereign over all non-human resources within its boundaries. Nations can protect their borders as a means to protect their valuable resources. However, this does not always work, such as Peru and the Cinchona seeds, whereby smugglers stole the seedlings – representing the power of the Western nations and them suiting their interests for the seeds but aggressively protecting their interest by restricting flows (politics of quinine stocks).

Therefore, have plants ever been public? If something is common material than it would grant freedom of access and use. If something is a common material than who is responsible for maintaining and conserving it? Bioprospecting also draws up the complications of responsibilities, especially coupled with globalisation. Regulating bioprospecting is paramount for the survival and conservation of plants, as well as protecting future interests and the possibility of finding cures.

A responsible bioprospecting architecture must:

Ø Recognise the different groups involved, including marginalised individuals and communities

Ø Recognise the non-human lifeforms involved in bioprospecting, and this highlights the profound entanglement humans have with biodiversity

Ø The urgency of collaborating with indigenous peoples before knowledge, language and biodiversity is lost, a result of climate change and globalisation.

Responsible bodies and organisations

1) International and global agreements

International bodies like the Convention of Biological Diversity (CBD) is a neoliberal, universal system which actively encourages bioprospecting. However, it disregards the unique ecosystems and territories which exist, as well as marginalise communities and their rights, rather promoting large Western pharmaceutical corporations. Some have extended this further and suggest that territory based bioprospecting, which instigates regulation and intervention, is best as it connects the local knowledges with broader struggles. Territorialisation itself undermines cultures which do not recognise territories and land rights. The UN Draft Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples reinforces the idea that bioprospecting means granting access to territories rather than knowledge. Territorial rights promotes greater autonomy and bolsters self-determination of local communities.

2) Localised agreements and funding

Localised agreements which would help indigenous communities from the discoveries and usage of harvested plant material in the pharmaceutical commercialisation. The myriad of connections and entanglement mean it is difficult to trace the links between local communities, pharmaceuticals and the circulation of plant and drug materials. Bronwyn Parry argues that keeping biological material under control is near impossible, especially with the new technological, economical and legal developments. The communities that supply the knowledge and pant material have yet to receive tangible pay outs, so an agreement should be made that they add a sum between 3%- 5% of their profit ratio to all these products that are collected natural materials. These margins should be contributed into a large fund which nations from the south can use for development projects.

3) Power to the people and national governments

This is being put into practise and is when Southern nations begin to recognise the value of their biodiversity, which they need to conserve, but also profiteer from. The ICBG-Peru project highlighted to the Peruvian government that it would not be the last time scientists would want access to their resources. those who wish to access the knowledge for commercial or industrial application are required to secure prior informed consent of those who hold the knowledge. A license is then required (non-exclusive) to guarantee access (at cost) and dedicate 0.5% of the value of future sales towards the Fund for the Development of Indigenous Peoples. This is in respect to knowledge in the public domain and indigenous people can make agreements still and request compensation. A Register of Collective Knowledge would also be created for which the National Institute for the Defence of Competition and Intellectual Property (INDECOPI) will take responsibility. Access to this register will require written consent of the indigenous peoples who own the knowledge. This way manages the access to knowledge and land, and means that the indigenous people are not exploited as everything is informed. It still permits the flow of bioprospecting and is an alternative to WTO structures.

A globalised world is continuously being made and remade, and bioprospecting is no different. Bioprospecting draws together international communities, and, requires a large amount of funding, technology and legal backing in order to find, source and research on plants to make them commercially viable. The key transformations involved in bioprospecting represent an interplay of territory and flow, i.e. defining territories, territorialisation and the flow of goods and knowledge. The creation of the global architecture remains to be contested, with the North still taking advantage of the South, but this is set to change.