Migration has caused a shift in identities, religion and cultures around the world. Some people may feel connected to areas they were not born in due to family history or ancestral links. Due to migration and demands associated with belonging, people’s identities can feel conflicted.

During the colonial period, and especially concerning the British Empire, nations shared a common language and had the freedom to move within the empire. It is also widely accepted that during and after war times, people moved to flee from conflict or rebuild and set up a new life after conflict. In particular, from the 1970s migration has become more significant and a pressing political issue, with regards of how to control, regulate or manage it.

In a globalised world, connections and mobilities across the world are intensified and enhanced. The migration of individuals and communities is causing a global shift and change in markets – while it somewhat undermines national boundaries. Migration is difficult to control, and it unevenly distributed for a number of reasons;

- Participation in trade blocs and deals with nations – this may permit the freedom of movement between trading partners

- War and conflict drive people from their nations into nations regarded as safer and welcoming

- Opportunities and better standards of living offered in other nations, which would be appealing to those living in poverty

- Cheaper and more available travel to and from nations, including more flights and modes of transport

However, migrants are often regarded as ‘alien’, ‘foreign’ or ‘unwelcome’ despite their contribution to society. Especially when there is an exodus of migrants, say from war torn countries, inhabitants get defensive about their culture, language and identity and often migrants receive a lot of criticism and aggression from inhabitants. Also, migration is not so easy and there are both physical and mental barriers to moving nation to nation.

It has been noted that in recent years’ migration has a negative stigma attached to it and many nations, in an attempt to defend themselves, have adopted policies to quell migration. States will also put up barriers or disincentives for migrants too, such as tests or trails or not having access to the same rights as citizens. Some migrants are constrained as to the extent they can travel, perhaps due to economic or emotional reasons, and they cannot just settle wherever they please.

What is ‘belonging’?

Belonging is to feel attached to, or have a mutual attachment too, a person or place. It can include feelings of possession and to own, or feel owned. In relation to people, belonging to a person or places comprises of a few factors we both choose and are automatically enrolled in. for example you cannot pick your family, name or where you are brought up. However, you can choose your interests, social groups or communities in many respects which are an extension of your identity. There are some communities we may wish to belong to but cannot, or we may live in a place we feel we do not belong.

Belonging is both a matter of choice and feeling, or something given or imposed on us. The sense of belonging gives a sense of relief and familiarity, but can also cause a sense of unease similar to a blessing or a curse. Ambivalent feelings about home are sometimes a key factor for migrants. They may not feel as though they belong to a community or state and may migrate as means to satisfy their feelings of belonging. Communication and the media can strengthen or undermine peoples sense of belonging.

The concept of distance

Throughout history people have migrated to other nations, and while most may stay, others may move on. Their children and their children’s children may do the same as well, causing a lot of networking and ties to other countries. Distance and proximity are therefore concepts created by humans which can be imposed or created. Although you have the physical geography of distance, i.e. so may miles away, the idea of distance is one that is a social relationship.

Citizens and states use various tools relating to the concept of distance to deter migrants from migrating, including refusal or denial of their connection or right to a place or nation. This denial can come in the form of social or legal reformation, culturally ‘placing’ migrants elsewhere or by asserting their differences. However, migrants can employ methods to exert their right to a nation or state, which undermines the concept of distance. This can be achieved by emphasising their historical roots to the nation, adopting a local identity and nationalism, or through long distance nationalism that applies to some nations.

Migrants themselves are often concerned with the emotional and cultural dimensions of proximity and distance, confirming to legal or social demands (like citizenship or culture). Migrants may feel compelled to ‘fit in’, which suggests it is a binary choice, you are either in or out.

Transnational migrants

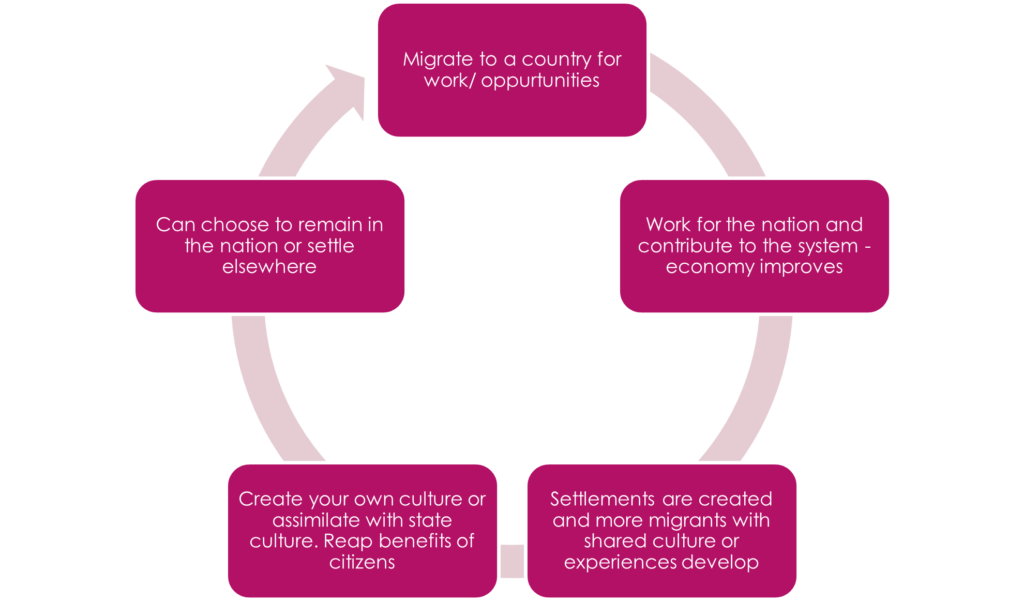

There are a range of factors that influence migration and where migrants choose to go. Different migrants have different capacities to move and settle, while some nations are more lenient. Migration is not one single movement, and can cause a snowball effect. Migrants are transient and move from one place to another within weeks, months or years. Moreover, their children can move as well.

Another thing to note as well, which makes migration ‘easier’, is moving families to other nations. For many, the ‘able bodied males’ will go seek work and send reparations back to their families. In time they can save enough money, and be granted citizenship rights, in order to move to other nations. Women, often seen as the home maker or care giver, would then move over in due course with children. Migrants therefore do not have to make a home of the nation, but simply bring their home with them. This creates a sense of belonging.

The concept of proximity and distance is also not set, like identity, and can change over time. The British Empire set up many links and networks that transpired space and time, while also contributing to cultural differences and unification. Citizenship of a nation state stills play a role in identity and migration movements regardless of globalisation. The feeling of belonging or abandonment contributes to where migrants go and settle.

Twice & Direct Migrants

Migration is not simply a one off journey, but migrants can move multiple times as can their children. Some will move to one nation and then move to another within the same generation, while others may migrate but with the intention to go back home.

Parminder Bhachu (1985) described East African Asians as ‘twice migrants’. Bhachu’s work focuses on Sikh communities who migrated from Punjab to East Africa in the early 20th century and then to the UK from the 1960s and 1970s. In East Africa near the end of the 19th century, around 32000 labourers were recruited to work on building the railway, and of those, 6500 stayed in East Africa due to the new opportunities in the area. This meant that the ‘free’ migration of Punjab Indians who travelled to East Africa to take up commercial and administrative opportunities, and the migration from East Africa denote migration is not a singular occurrence.

The East African-Punjab Sikhs who migrated are significant for a few reasons;

- They had no marked orientation to a ‘home country’, either from Punjab or East Africa. Migrating to East Africa gave them a different experience, different to those ‘direct migrants’ who travelled to the UK first. Those who moved first had deeper ties to Punjab.

- They became a settled community and the Punjab labourers had already had their own networks and resources. Going through colonial education system shaped their technical and cultural skills – this made them valuable assets and prosperous migrants.

- Varied experiences of migration and national events can shape public opinion and sense of belonging, uniting or fracturing relationships. The Golden Temple in Amritsar (1984) was burned down, and this led to the mobilisation of a Sikh force. It did not matter where the Sikhs were, they united for a common cause for a common land.

As a result, those who migrated straight to Britain found it quite difficult to assimilate or feel a sense of belonging as they were always tied to their home nation, with the intention to return. In contrast those who migrated to East Africa and then onto Britain had better linguistic skills and ability to fit in due to their experiences – they were also skilled making them an economic asset. Furthermore, with the lack of ties to India, those migrants who went the East Africa beforehand felt more inclined to settle in the UK as they felt less ties. When the burning down of the Golden Temple in Amritsar occurred it showed that no matter where the Sikhs came from, their historical ties or their caste, they would have the ability to prosper in a new society.

By the 1990s these migrants have moved onto the likes of USA, Canada and Australia. This is largely possible because of their skills and abilities that they have honed during migration. The familiarity of the English language and bureaucratic institutions of the West also helped them to move from place to place.

Indian Independence (1947)

In the early part of the 20th century people in India protested about discrimination against Asians in East Africa. This demonstrates a connection with their Indian counterparts. Likewise, the East African Asians expressed solidarity with the Indians during independence.

After independence the attention of the Indian government was not on the migrated Indians, but the nation itself and forming a state. The expatriate Indians could not have a say in how the Indian nation formed. East African Asians were encouraged to settle where they lived, and for both economic and political reasons, they chose not to take the citizenship of the newly independent countries of East Africa. The migrants were therefore left in limbo as they neither belonged to the Eastern African states or India. The decision to not take on the African citizenship demonstrated distance in the place they lived, but also their homeland. Despite taking on the identity of ‘East African Asians’ for many this identity was shallow, no matter settling, learning and intermarrying.

African Independence (1960s)

The independence of many East African states in the 1960s mean that the Asian migrants were left in an odd situation. They could not be citizens of India, nor were they fully part of Britain. After 1947, they were classed as British subjects who were part of Britain and its colonies.

The British Immigration Act (1962) meant that an issue regarding citizenship arose. The act made it more difficult for groups to migrate and settle in Britain. Although the migrants could return to India where they shared a language, the benefits of Britain economically far outweighed India. The schooling of East African Asians, including language, made Britain feel closer to home for many migrants (proximity).

In 1968 the British Government announced that it was planning to impose migration quotas. This caused many East African Asians to migrate before this quote came into power. Alongside this, India said it would deny those with a British passport as they were no longer deemed the responsibility of India. India did however permit the entry of some Kenyans who were restricted to owning property and investing in business.

In 1972 the Ugandan government led by Ili Amin decided to expel Asians from the country, displacing them. As India relieved itself of responsibility, they were unwilling to assist. The British media warned of an invasion of their once ‘subjects’ and famously Leicester issued warnings against those thinking to settle. The underlying message was the migrants were no subjects of their homeland India, not of their working country Uganda, while the expire did not want anything g to do with them. The East African Asians, recognising that Britain was affluent and powerful, leveraged their rights as a British subject in order to migrate there in the 1970s.

Migration & Tensions

Migration typically causes tensions as the inhabitants may feel pushed out, and the same can be said for the migrants. However, the goal is the same, to reap better opportunities to better oneself. The slogan ‘send them home’ denotes a sense of entitlement and belonging, as well as exclusion for those deemed not part of the country.

Pro-Nationalist parties promote sending migrants, or ‘them’, home, i.e. a nation considered their country of origin. However, as we know, ethnicity and race doesn’t dictate origins, but helps impose them. The refusal of proximity and hostility suggests that you are either in or out, but we know the relationship is not as simple and instead is more fluid.

Identities can easily be formed near or far the member nation, i.e. citizens can be educated in the US or India and still ‘come across’ as English. This suggests that culture and identity is not so sacred or confined to the nation state, but can be replicated and moulded to suit needs. In the same way, people can be brought up in their home nation but still ‘rebel’ conventions or take it to the extreme, such as young militants who take on religion to the extreme despite being brought up liberal.

Another issue some migrants face is the feelings their culture is challenged. For some they do not adopt the nations customs and culture, and as such feel challenged. Some migrants withhold concerns that the home nation culture is a ‘corrupting’ or undermining their for identity. The’ westernisation’ for some migrant children can cause conflicts or crisis of identity, where the parents feel closer to a distant nation in contrast to their children who could not be further from it. The cultural and emotional proximity that some migrants feel for their places of origin may seem remote for their offspring.

The void left by leaving their home nation is not necessarily filled by occupying another nation. For some, the distant nation they left feels closer than the nation they occupy. When cultural or political events occur it also strains the feelings of proximity and distance. For some they may feel a sense of solidarity with their home nation and very connected. There also may be senses of relief that they are not there or fear for loved ones.

Different genders are also impacted differently by migration. For many, able bodied males are the first to leave the home nation and settle elsewhere. They would then bring the family at a later stage, and the family ‘make the home’. This helps consolidate the sense of belonging.

There are various senses of belonging which vary amongst most migrants, and often it is a consequence from roots and routes. The sense of belonging varies with the generations as well, with some belonging to a local, national or transnational identity. Near and far mean different things to different people. For some migrants they may feel closer to their home nation, and it is the sense of belonging that is not so simple. The feeling of not belonging anywhere, as in they have left their home nation but do not feel involved in their current nation, can also affect the sense of belonging.

Home and Away

Migration is not set, and it has impacted different nations in various ways. There are changing relations between the countries where people migrate to and from. The state exerts some influence in who can and cannot settle in areas, as well as what kind of citizenship they are entitled too.

The state can construct migrant senses of proximity and distance through institutional and political processes. Nations can attract certain individuals, and equally deter those deemed undesirable. This creates a pull factor for some migrants, and, some may aim for these destinations by learning a particular sector. Likewise, home nations need to challenge ‘brain drains’ or loss of its workforce by incentives for citizens to stay. Migrants are selectively pushed and pulled from their country of origin – the state wants their affluence, but does not want to grant political power. Identity and belonging are linked to and rooted in more than one place, and physical proximity or distance play a reduced role in the sense of belonging.

Migration in a globalised world

In a globalised world proximity and distance are entangled in migrant lives. Matters of identity, belonging and home are connected to proximity and distance – which are subject to change. Migrants express a sense of belonging to one nation while remaining their loyalties to their home nation. Migrants can and do sustain connections between these places asserting that they are near and far.

Migration is a large network around the world. These connections are further extended by family or social ties. These connections spanning across borders mean there are greater demands for migrants to belong. Migrants are mobile beings and can belong to more than one place. They can feel close to home far away, or distant and lonely in their current nation without rights.

Migrants can be mobile and exemplify the idea of transnational migrants and globalisation. Migrants are flexible and un-rooted being able to travel and settle wherever. However, although they can be free, it also relies on the ability to settle and make a home. They need the skills and ability to make a home and build a community.

The state plays a big role in migration and what migrants can accomplish. The state dictates who can enter the country, control where they go and attempt to identify them as well. This can cause tensions as the migrants contribute to society, but can rarely reap the rewards or possess political power. The governments are happy for migrants to pay tax and invest in the nation, but will not submit to demands for dual citizenship. This creates a sense of proximity as they are engrained in communities, but distant as they cannot make a difference.

Roots and routes create identities and a sense of belonging. Although routes is generally seen as more open and flexible, and less based on history, they still concern the deep connections between nations. The concept of belonging or not as not as simple and is based on a variety of propositions – it is contingent. Proximity is created by a combination of cultural, economic and political factors.